If you don’t have gratitude, then no matter how much you have, you’re poor. Because you’re always looking at what you don’t have. If you have gratitude then you are never not wealthy.

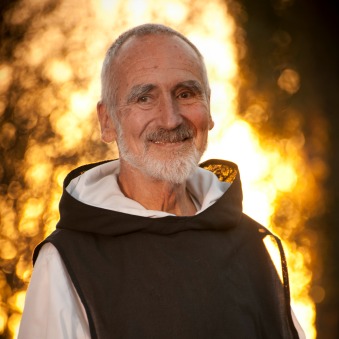

Br. David: Sometimes it’s difficult to track this little “me” down. It’s quite evasive, because we identify with it. It’s quite evasive. One way of tracking it down is catching it when it complains, and there’s where the complaining comes in. It has a habit of complaining. So since you mentioned this word complaining, I’d like you tell us more about complaining.

Roshi Joan: No, no.

Br. David: Then I will tell you something about complaining too, but start us off. Would you like to take this with you?

Roshi Joan: Oh sure. I actually thought about complaining because I don’t know if it was you who told me this wonderful story, or whether it was the person it’s about. The story’s about a billionaire, that always catches our attention. The billionaire was asked, “What is the secret to your wealth?” And the billionaire said, “Gratitude.” Then he went on to explain if you don’t have gratitude, then no matter how much you have, you’re poor. Because you’re always looking at what you don’t have. If you have gratitude then you are never not wealthy. Did you tell me that, Brother David?

Br. David: No, I didn’t.

Roshi Joan: Oh, it’s very good.

Br. David: Maybe the billionaire told it to you. You move in those circles.

Roshi Joan: So do you.

Br. David: On occasion, yes.

Roshi Joan: Yeah, we’re the mendicants in the circles of affluence, you go in like a migrating duck and go out. Quack quack.

Br. David: That’s very beautiful.

Roshi Joan: Yeah. In Zen we have an expression, which I think is really beautiful, about our, it really refers to our psyche. It refers to our psyche as a treasure house. I remember when I was working at the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center, working with my ex husband Stan Grof, using LSD as an adjunct to psychotherapy with people who were dying of cancer. I was so amazed about the profound wealth of the human spirit in circumstances which for most of us would have seemed utterly daunting. That wealth wasn’t necessarily accessed by the people in our program until they were given a lot of support and preparation, and then they had this psychotropic substance and went through a very deep mystical experience, and came out at the other end of that experience with a sense of their fundamental enrichment. It kind of changed my heart and mind, because I had felt that somehow the human spirit was limited.

Then it was through the practice of Zen, not so much the practice of drugs, but the practice of meditation over many years, Brother David and I having a similar Dharma birthday, over 40 years of sitting, that this sense of plenitude in a world that feels it is perceiving itself as impoverished.

We have to reassert the sense of plenitude because it is the sense of impoverishment which has ripped off resources out of the deep sense that there’s just not enough for me.

Roshi Joan: I think also about this in relation to altruism, which is a very important value in our community, and I’m speaking about this whole community. I know many of you here. I know how much many of you give. I know how much you give, Phyllis and how much you give, Susan. It’s so nice to see the two of you. I know that altruism characterizes your life in a very deep way. And you, Howard and Liesel, how much you have done for me and for our community and our whole network and Dominic and Dick, and so many others in this room. Not to say that there are only half a dozen, it’s more like 40 altruists here.

I know that there is this deep sense that I was brought up with, that is fundamental to Zen practice and to Buddhism and to Christianity. It’s fundamental to all deep religions that benefiting others is really essential. The benefit to others comes not only in terms of our direct actions, but also comes in terms of our attitudes because I’ve met some pretty grumpy, psychically impoverished, wiped out altruists and I’ve been one myself. It’s a very interesting thing to grapple with that paradox in your life and to realize that this is a very deep pattern in our culture. It in a way operates out of what David Aberle calls the principle of the limited good. That there’s not enough good to go around, so we have to look like we have less so as not to invite envy and jealousy in our village. These are old. I’m not just speaking about patterns that are 20 and 30 years old, these are village patterns from the Paleolithic.

These are patterns that exist in indigenous cultures where we can’t look like we’re too happy or have too much because we will invite jealousy. But really for the health of the planet, we have to reassert the sense of plenitude because it is the sense of impoverishment which has ripped off resources out of the deep sense that there’s just not enough for me. We are in a way manifestations of hungry ghosts. People who feel that I’ll never have enough. I’m never going to be rested enough. I can’t do enough. There’s not enough. Thich Nhat Hanh talks about this walking in Plum Village looking out at all these western faces and seeing so many hungry ghosts with a deep sense of not enough or lack of satisfaction or not being in the now as present. So that we’re asked to really turn the tide away from this conjured, but in a sense, archaic unhappiness and sense of insufficiency and to really not cultivate a mind of poverty in ourselves and through our complaining, also not cultivate that mind in others.

The conversation continues next week with these wise elders’ thoughts on a complaint-free world and change…

Roshi Joan Halifax – Buddhist teacher, Zen priest, anthropologist, civil-rights activist, and author – is Founder and Abbot of Upaya Zen Center in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Br. David and Roshi Joan have been friends since the ’70s. This conversation took place in May, 2007.

Comments are now closed on this page. We invite you to join the conversation in our new community space. We hope to see you there!